If Hinduism has the Vedas, Christianity the Bible, and Islam the Qur’an, which body of texts constitutes “scripture” for Buddhism?

Answering this is not a straightforward matter as Buddhism - like all major spiritual traditions - has a history of splitting into various sub-traditions and schools, each of which regard a particular body of texts as “authoritative” to varying degrees. What’s more is that during the Buddha’s time (c. 5th century BCE) the manner of transmitting his teachings was done through oral recitation and memorization, and the earliest written record of these teachings can only be dated to the 1st century BCE and afterwards.

If, however, we were to pose our question differently and ask: is there a complete collection of texts that survives today which best represents what the Buddha may have actually taught? The answer, fortunately, is yes.

The collection I’m referring to is known as the Pali Canon or the Tipitaka which has been preserved by the oldest Buddhist school that survives today: the Theravada school or “The School of the Elders”.

Why exactly we can regard these texts as the closest representation of the Buddha’s teachings is a matter that I’ll write about in more detail elsewhere. The major point to note here is that the Pali Canon represents the Theravada tradition’s version of the same teachings recorded, maintained, and adhered to by the original monastic community - known as the Sangha - formed by the Buddha himself.

The language in which the Pali Canon was originally written is known as…Pali, which is a Middle Indo-Aryan language “closely related to the language (or, more likely, the various regional dialects) that the Buddha himself spoke”.1

The Contents of the Pali Canon

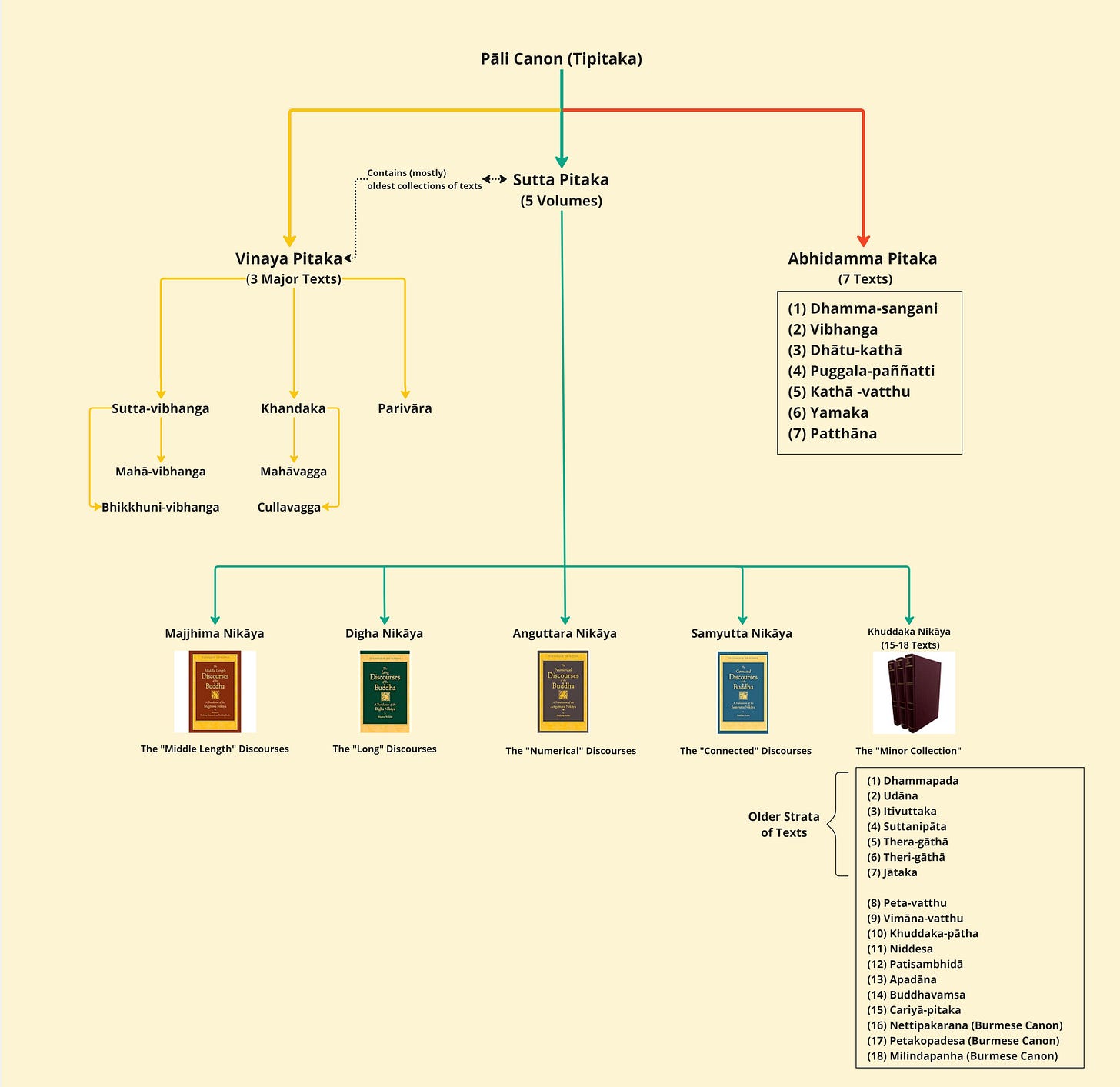

The Canon not only contains the vast discourses of the Buddha and his disciples, but also describes in detail the codes of conduct for members of the Sangha (monastic community), as well as a whole array of texts which attempt to rigorously systematize the original discourses. Broadly speaking we can categorize the contents of the Pali Canon into the following three divisions known as “collections” or Pitakas:

Vinaya Pitaka - Contains the rules and regulations for the Buddhist monastic community.

Sutta Pitaka - Contains the discourses of the Buddha and his disciplines.

Abhidhamma Pitaka - Contains a later collection of scholastic texts which systematize the Buddha’s teachings.

The Vinaya Pitaka can be further subdivided into three major works: Sutta-vibhanga, Khandhaka, and Parivara. Each of these deal with a vast array of rules for the Buddhist monastic community along with commentaries regarding the specific duties and modes of conduct for monks and nuns. This collection stands, alongside the Sutta Pitaka, as the oldest portion of the Canon and the two collections together constitute the Buddha’s entire framework for his teachings: Dharma-Vinaya.

The Abhidhamma Pitaka, as mentioned earlier, is considered to be a later collection composed of 7 works that are of a much more “thorough” nature than the discourses presented in the Sutta Pitaka. They cover an immense domain of topics dealing with the description, categorization, and interrelations of various mental phenomena and the nature of reality and are intended for the more philosophically (taken in its formal sense) minded.

With that being said, the core of the Buddha’s teachings that come from the Tipitaka, those which are most often referenced and followed and which are directed towards all audiences, are contained in the Sutta Pitaka. It is from this collection that we have access to what can be genuinely regarded as the oldest compilation of Buddhist teachings. It is the texts in the Sutta Pitaka which form the base of this great tradition.

I will, in a separate post, outline the various texts known as the Nikayas or “volumes” in the Sutta Pitaka , but for now I’ll just state that there are 5 in total.

So then, hopefully we’ve cleared up a few things regarding the oldest complete and extant literature that best represents the actual Buddha’s teachings. I’ll be writing a more detailed overview of each Pitaka in future posts, but for now I’ll provide a graphic below outlining the Canon in its entirety.

Check out my other posts on the Pāli Canon:

References

Bodhi, Bhikkhu. In the Buddha’s Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pāli Canon. Wisdom Publications, 2005.

“Guide to Tipitaka.” Edited by Ko Lay and Editorial Committee, www.budsas.org, Burma Pitaka Association, 1986.

Notes

Bodhi, Bhikkhu. In the Buddha’s Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pāli Canon. Wisdom Publications, 2005, 9.